Ole John's Groovy Buzz

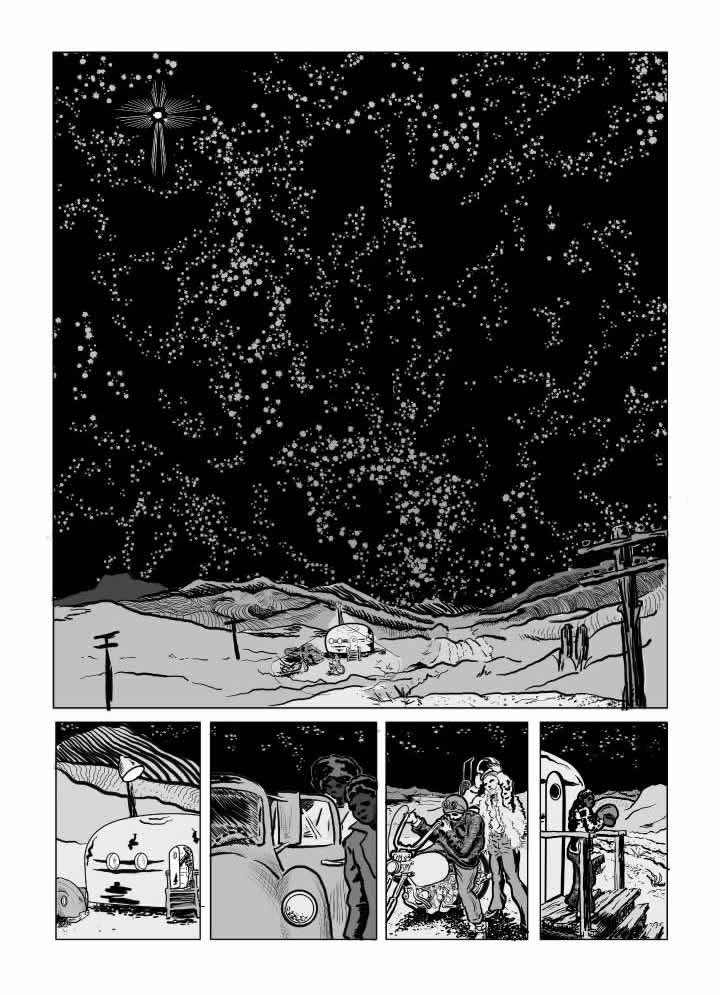

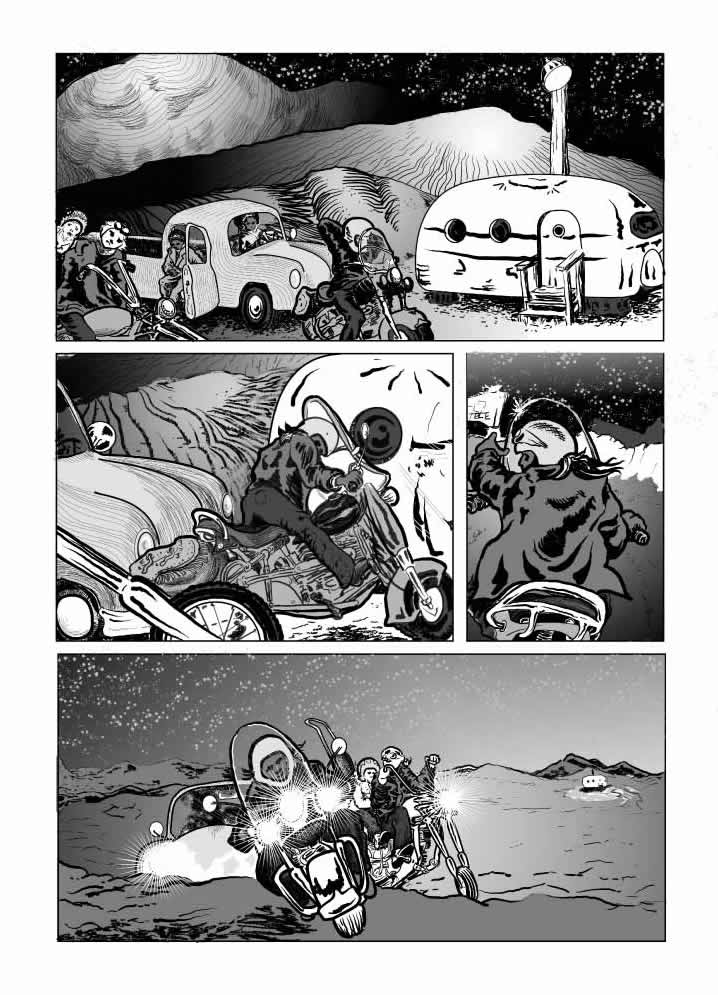

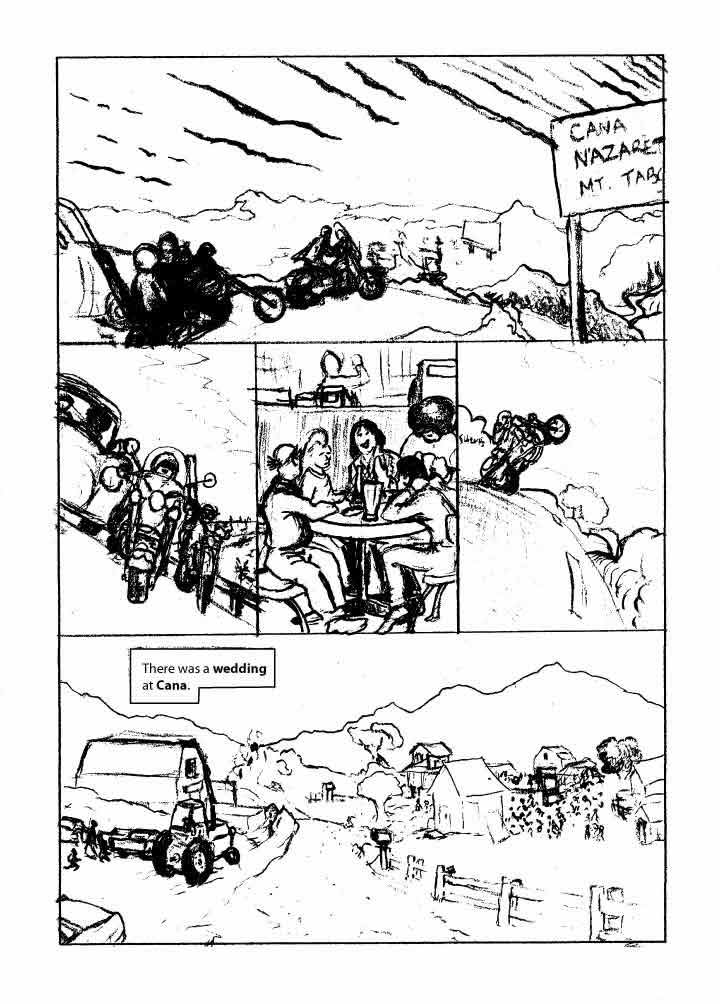

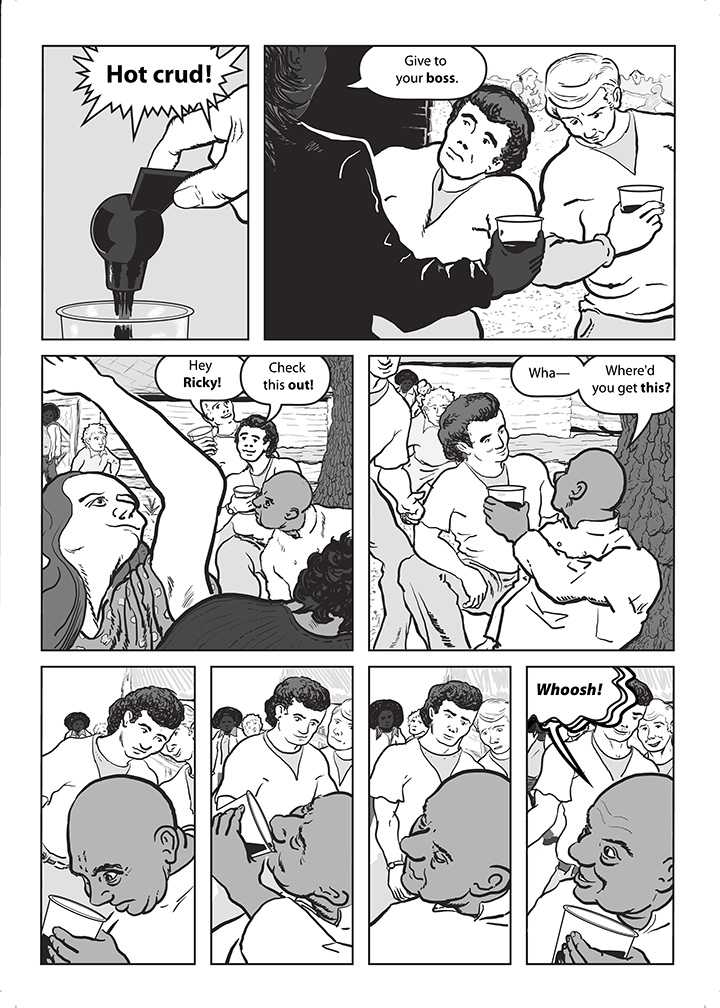

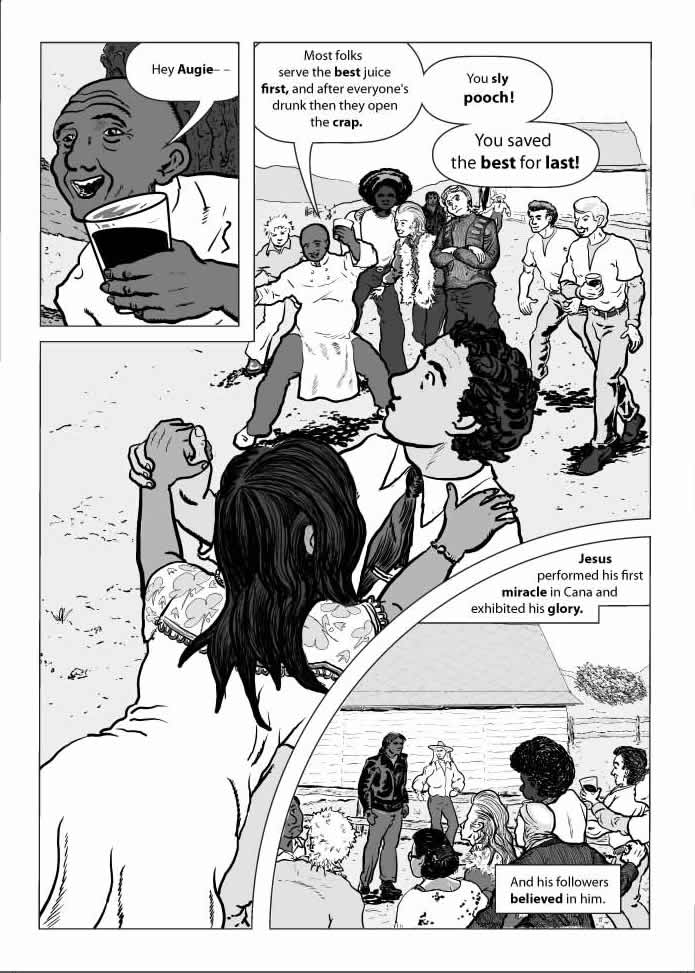

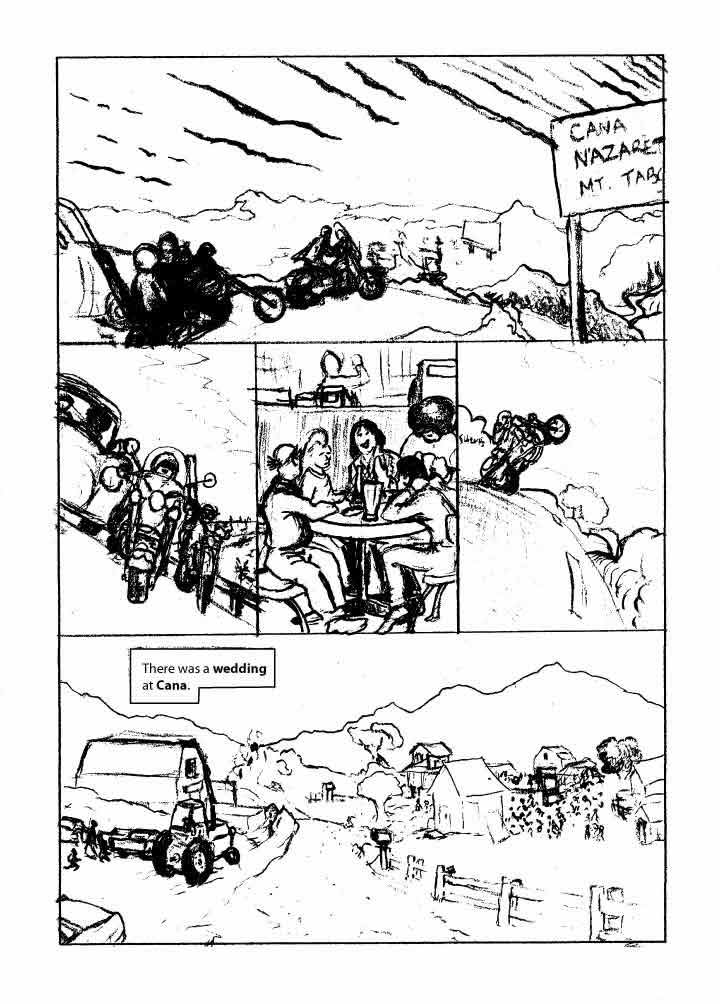

Wedding

Weddings are commencements, or so we hope, then why end here?

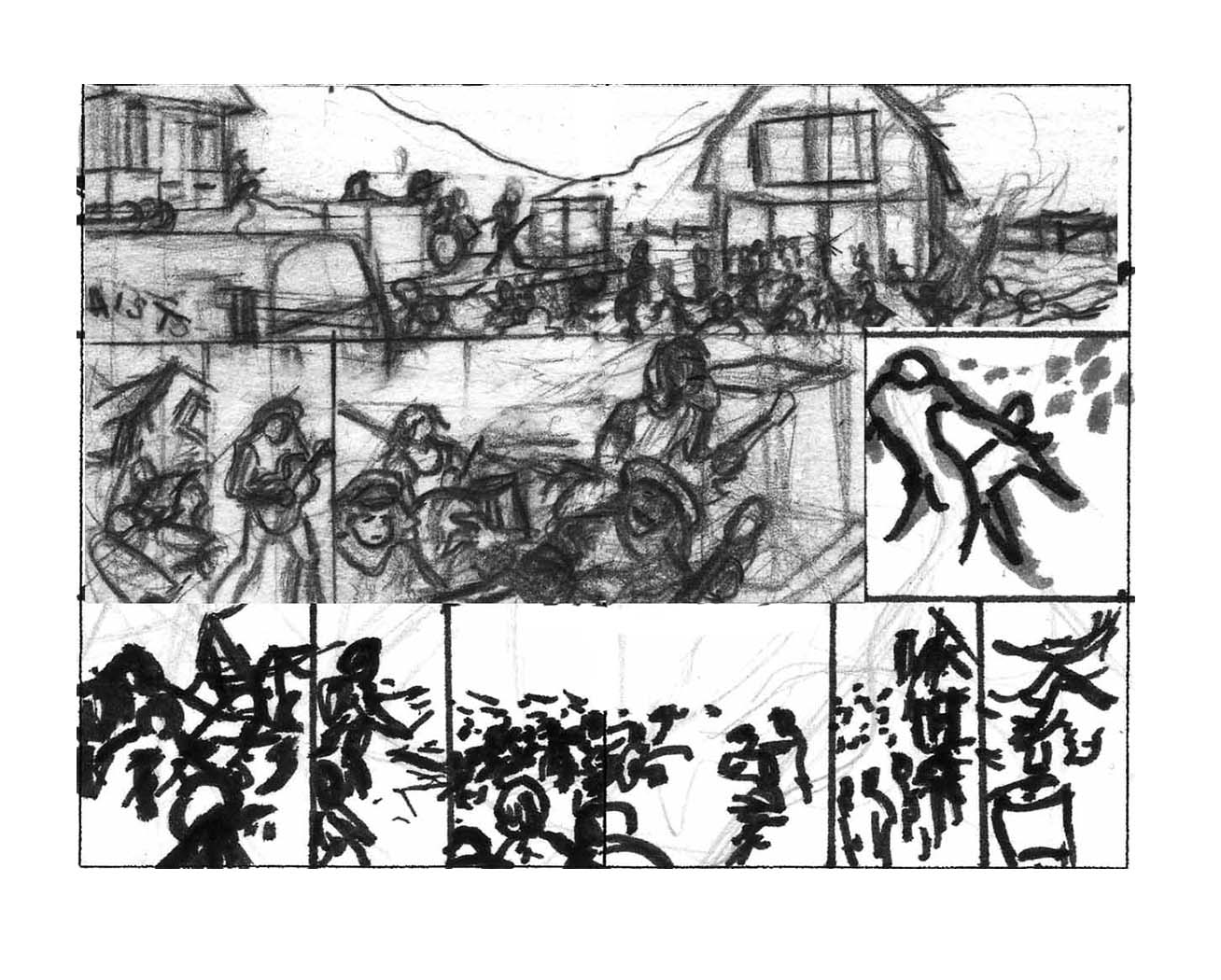

True, my posts lagged. You can see how unfinished pages went up just because it was Tuesday night, ready or not. If I had posted less often, say a page every other Tuesday, now twelve years out, the comic could have adapted the entire gospel, had I determined that to be my mission.

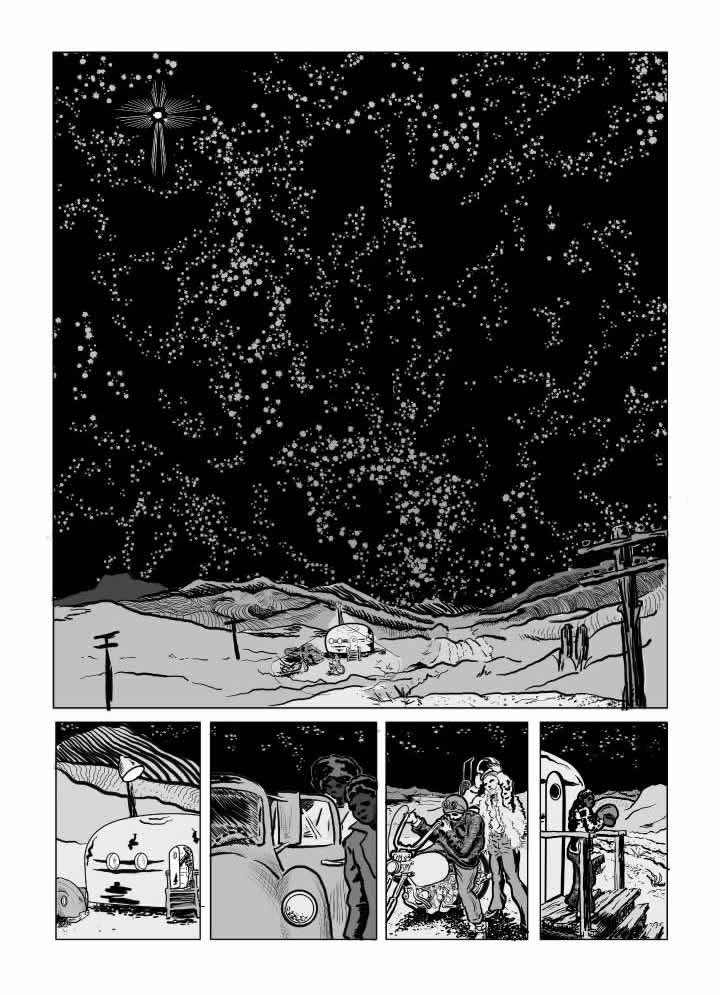

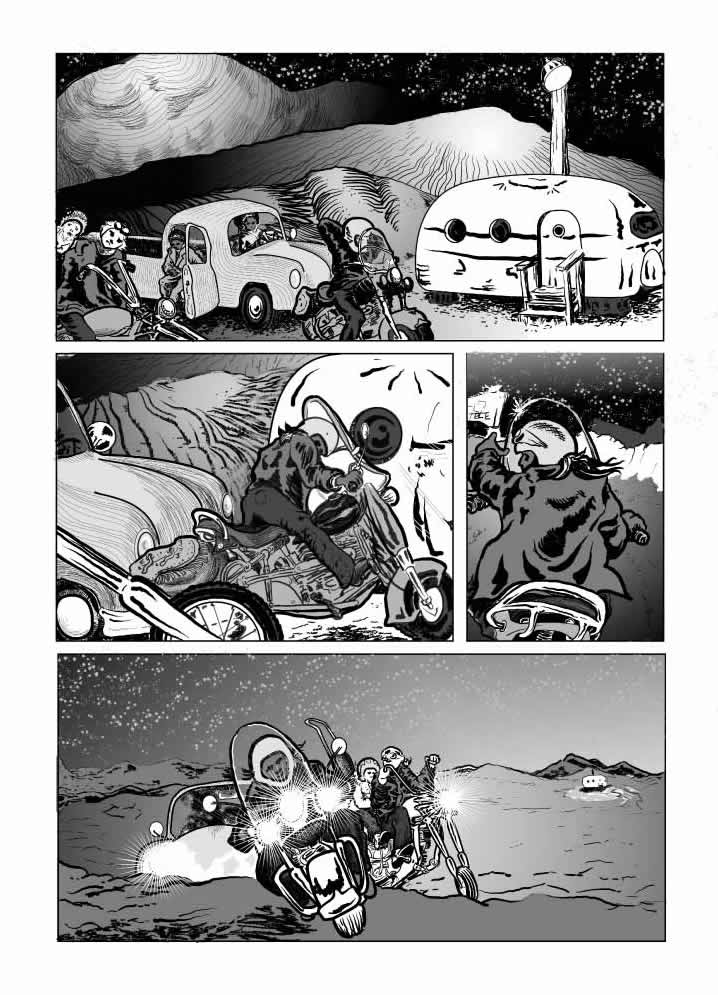

Behind the scenes, I started to write a different take, that take led to another, and I’ve found myself framing a different direction for Evocata and with it Ole John's tale.

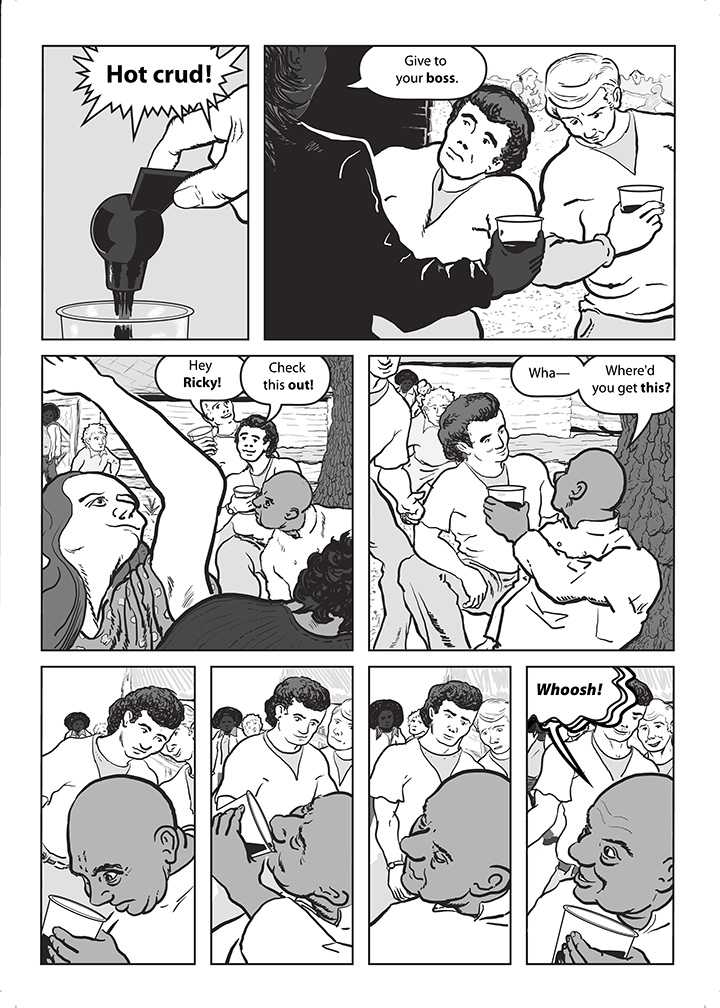

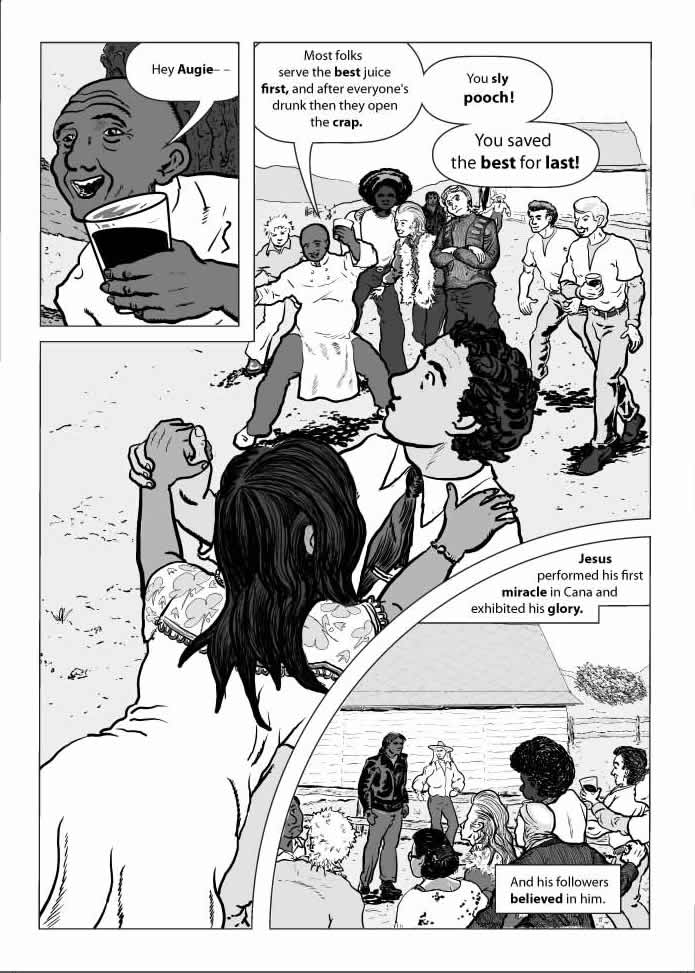

This episode, in fact, illustrates the sort of thing that didn't ring true and prompted a rethink— true in that weird way that counterfactuals in fiction can offer insights into our affairs, along with amusing us. What self-respecting Lakota messiah, even one who hangs out with hippies, would show up at a reception and furnish wine? No, this Jesus would not have played tricks with fermented beverages.

***

Set aside how this comic fancifully depicts the story, why does the Jesus of the gospel attributed to John turn water into wine, anyway?

While water sustains life, wine elevates the psyche. Besides its transformative effects, wine is itself a transformed substance, as mysterious in its nature as the blood it becomes in the sacrament. Of the four gospels received into the New Testament canon, this one, attributed to an early pillar of the Jerusalem Church, presumably in order to justify its inclusion, most emphasizes the nature and transformations of the Logos, a pre-existent aspect of the supreme God. It's the only canonical gospel to highlight the transformative second birth that Paul, the early missionary, makes so much about. Water into wine symbolizes this transformation, which the John gospel’s Jesus, in a subsequent story, will explain is necessary to enter the kingdom of God, blowing the mind of the inquisitive scholar, Nicodemus.

Yet the second birth motif also widely appears in the era’s popular pagan cults. Whether or not, as tradition has it, that the John gospel originated from a congregation in Ephesus, whose temple to Artemis attracted worshippers from far and wide, this gospel reflects its Hellenistic environment, one dominated by Greek as the most common language. Greek myth, art, and literature furnished major cultural touchstones familiar to both the John evangelist and his audience. Motley ideas, attitudes, and motifs originating from across the empire and from well outside it also exerted influence, as did the administrative and legal regime or the Roman state. Even though born and raised in a Jewish tradition, the John author, whoever he was, would have had a basic knowledge of the city's prominent non-Jewish religious traditions, just as rabbis in Rome today possess at least a sketchy understanding that Jesus’ cultural importance involves a manger and a cross. Indeed, such a modern Roman could possibly tell you more about Jesus than most Christians know. Besides his theological motives, the John author borrows from stories that Dionysus filled huge jar with wine out of thin air or commanded wine to flow from fountains, but he swaps protagonists, quite likely so Jesus can compete with Dionysus in the imaginations of converts, who would have known the myths depicted in mosaics, carved in stone, acted in the theaters or who had even participated in Dionysian rituals themselves.

Since the grape vine represents Dionysus, the John author has Jesus claim to be the “true vine” (John 15), as opposed, presumably, to the false vine, the wine god.1 Jesus does differ from Dionysus in many respects, despite their striking similarities2, and the gospel author tacitly alludes to Dionysus probably to set Jesus up as the anti-Dionysus.

For long before Jesus was heard of, people had understood that Dionysus had created wine and takes possession of those who intoxicate themselves with it, when they and Dionysus become one.

Although torn to shreds by titans, Dionysus was born again through a coupling of Zeus and the hapless mortal woman Semelé. The inexact, though striking resemblance of Jesus, proclaimed the first-born from among the dead, to other dying and rising gods honored among the goyim, gods which included Osiris, Tammuz, Attis, Ishtar, Persephone, Hercules, as well as Dionysus, presented a recurring scandal for Christians who had to fend off charges of religious plagiarism. The apologist Justin declared that the wily and prescient Satan, foreseeing what was coming, devised bogus salvation cults, centuries before the fact, to snare the unwary with sacred tales and sacraments similar to what Justin’s sect would later preach and practice. That the travails and triumphs of such gods informed the evolution of a Jewish Christ myth is more probable.3, 4

Don’t get me wrong. Paul and other apostles did believe that God assumed human form as Jesus, whether through extracting matter as he descended from one layer of Heaven to another, through enveloping a man with the Holy Spirit, or through conceiving him upon the virgin Mary. As far as they were concerned, Jesus suffered and died. God really did restore him from death, now in a “celestial” body. Not caring about what supposedly happened that involved those other gods, the apostles took this as the real deal.5 Whether or not they had ever known in Galilee and/or Judea a pre-crucification Jesus, they understood that post-resurrection visitations of Christ happened on earth, because they happened to themselves. Paul even provides a list of appearances (1 Corinthians 15). He didn’t just know the Christ myth as a pretty story. He inhabited the myth. It was his reality.

Just as different myths shape reality for other kinds of believers. It’s a pretty safe bet, in line with experiences reported across religions, to assume that at least some of those who partook in the Eleusinian rites felt themselves touched by Demeter or Persephone. A few in awe and terror may have even thought they’d glimpsed one of them in one of the many guises deity can assume. Whether or not there be affairs in Heaven and Earth undreamt of in secular cosmology, I leave open to further discovery, albeit with measured skepticism, yet I’m more persuaded that astonishing matters remains ill understood in human psychology.

1http://www.academicwino.com/2020/12/wine-myths-dionysus.html/. Accessed 28 September 2022. For general information on Dionysus, his Wikipedia page is as good a place as any to start. Robert Graves in The Greek Myths compiles much of what the classical literature has to say, though without the context of the many findings of 20th and 21st century archeology. Euripides's tragedy The Bacchae presents the young god introducing his worship even though the mortal establishment of the city Thebes opposes it. Many parallels The Acts of the Apostles shares with the play suggests its literary dependence on Euripedes. vridar.org/2013/08/26/jesus-and-dionysus-in-the-acts-of-the-apostles-and-early-christianity/#more-44064

2The late D.M. Murdock (Acharya S) lists the points of resemblance at stellarhousepublishing.com/dionysus/. Accessed 28 September 2022.

3In contrast with Justin, the third century theologian Origen viewed the pagan myths as garbled revelations of the divine plan, either given to the Gentiles and scrambled, or vaguely inferred by their fallen spiritual intuitions. In this, Origen may have reasoned along similar lines as Paul does in Romans 1, who probably draws inferences from Psalms 19:1, “The heavens declare the glory of God and the sky’s vault exhibits His handiwork.” Paul judges that God reveals enough of Himself and his invisible attributes, just by creating the world, to leave humankind without excuse should they practice idolatries, willfully mistaking such visible entities as the sun, moon, earth, sea, streams, or trees for ultimate divinity. The characterization of nature as a book of God without words, as elaborated in both Jewish and Christian traditions, surely influenced Spinoza’s rival concept of God as the Substantiva from which all other existence is its finite modifications.

4I use the terms “myth” and "cult" primarily in their neutral, anthropological meanings. A cult is a circumscribed group that shares a common culture, strongly distinguishing insiders who get it from those on the outside who don't.

"Myth" is the coherent system of metaphors, allegories, and tales, not necessarily erroneous, that a cult shares, discusses, and celebrates. A cult often shares rituals that re-enact the main turning points of its myth.

Not that this is a one way street. Poets reply to priests, though they may risk being silenced. In crisis, however, poets can sometimes be retrospectively celebrated as revitalizing visionaries. To complicate the picture further, poet and priest can reside inside the same skull. The second Isaiah and the John author are instances of this.

5It hasn't been the rule in world religion that a god's death or descent to the underworld should accomplish an atonement. Some gods die during the course of strife within the society of gods. Persephone falls prey to another god's lust. Balder perishes from a trick Loki plays on Hodr. The arrogant Inanna is imprisoned and executed after failing to seize command of the underworld from her sister, yet afterwards allows demons to drag her feckless husband, Dumuzid, down to the realm of the dead as her substitute when she finds that he has been living it up in her absence, neglecting to mourn for her. More often than not, a god's return revivified the natural world with the arrival of rain and in cooler regions warmth. Yet the cults of Osiris, Persephone and several other deities did come to promise some type of enhanced state during the afterlife.

Both Hebrew and gentle assumed that whatever gods there were, they must be placated with sacrifice, with the sacrifice of a human constituting the most potent offering, as when Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia to appease Artemis, so she would release the winds Agamemnon's fleet needed to pursue his payback enterprise of pillaging Troy. The Greek authors viewed this as an extreme measure, with Aeschylus portraying the victorious Agamemnon finding death dealt by a mother's vengeance, rather than sincere welcome from a wife, when he returns from his war. The Torah's quick resort to capital punishment to blot out real and supposed evils from gaining social acquiescence can be interpreted as a kind of human sacrifice, warding off the god's judgement.

Nonetheless, Y---ist Hebrews came to believe that their god had repudiated the offering of the first-born (Exodus 13:11-14, Ezekiel 20:25-26), deeming other cults' ritual slayings of children heinous (Leviticus 20:2, Deuteronomy 12:31, Ezekiel 15:20-22), though the story of Abraham's willingness to sacrifice the son of promise, at Y---'s request, serves as a reminder of darker times.

The first Christians saw the Abraham and Issac story (Genesis 22) as a type that pre-figured the sacrifice of Christ: As Abraham was willing to slay Isaac to please his god, so God the Father was willing to allow his Son to present himself as an offering for the sins of many, as though God had to placate Himself, as though justice had become a rock He could not lift without taking extreme means. Or as though looking over his shoulder at what humans might think, should He merely forgive those who harmed them without somebody paying some kind of recompense.